By Drew Harris

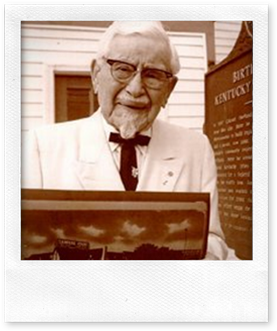

How delicious are those 11 “secret herbs and spices” assembled by Harland Sanders in 1930 for his popular “Kentucky Fried Chicken” sold at his local service station? It was so “finger lickin’ good” popular that the Governor Ruby Laffoon proclaimed him a “Colonel” and he started franchising his chicken business. But rather than patent the recipe, he chose instead to keep it a “secret” in order to protect it. The KFC Original Recipe is, in fact, perhaps the most famous and notable trade secrets in history.

In order to protect the ingredients, the secret original recipe, handwritten and signed by Colonel Sanders himself on a now yellowing piece of paper, is held in a special segregated company vault in Louisville, KY, along with 11 viles of the ingredients for good measure. Throughout time, it has only been seen by a handful of employees (all of whom must, of course, signed ironclad pledges of confidentiality). The vault itself, which can be accessed by only two people working in tandem, is monitored around the clock by video and motion-detection surveillance systems.

To further insure that the secret remains so, the 11 herbs and spices are mixed in separate halves – one half by Griffith Laboratories and the other by McCormack – and then combined together all at once by the latter to ensure that nobody outside of the companies should ever know the incredibly lucrative blend.

Many have claimed to have discovered various versions of the Original Recipe, one of which was published in the Chicago Tribune, however KFC maintains that those are not even close. The ability to maintain the secrecy of the Original Recipe is paramount to the business of KFC, and establishing it as a trade secret offers the fast food giant the best protection. If KFC (or their parent company, Yum! Brands) were to have patented the Original Recipe, the recipe would’ve been published, and made available to the public after the expiration of the patent, allowing anybody to copy the secret recipe verbatim, which would dramatically devalue the KFC brand.

The story of KFC illustrates that trade secrets are very lucrative commodity to U.S. companies such as McDonalds, Coca-Cola, and many others. That is why the Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016 (the “DTSA”) was an important piece of legislation. The DTSA is a powerful tool for companies like them that ferociously defend their trade secrets.

A Brief History of Trade Secret Protections in the United States

Protecting Intellectual Property has long been important in the United States, and indeed internationally as well, however trade secret law has historically taken the backseat to copyright, trademark and patent law on a federal level. Until 2016, with the passage of the DTSA, trade secret law was handled exclusively on a state-to-state basis, with statutory law differing in respect to statutes of limitations, definitions, application, and other relevant criteria. Companies were required to jump through certain hoops established variously by state legislation and court precedent to establish a trade secret.

Some progress was made toward uniformity in 1980, the Uniform Trade Secrets Act was approved by the American Bar Association. Nearly every state that has enacted a trade secret law has adopted the UTSA (New York and Massachusetts being the two states with trade secret law that have not). Another reference is the Restatement of Trade Secrets, which provides a summary of the varying trade secret laws passed in states throughout the US.

In 1996, Congress passed the Economic Espionage act (EEA), the target of which was stopping trade secret theft by foreign governments, individuals, and entities in general. While the EEA did provide a step in the right direction concerning Federal legislation regarding trade secret theft, instead of provide a private cause of action the EEA instead relied on the U.S. Attorney’s office, which was already strained.

Finally, in 2016, the DTSA greatly altered the way in which U.S. companies can seek remedy for trade secret misappropriation and changed the legal landscape of trade secret enforcement in the following ways:

1. U.S. Companies can now hire their own lawyers

Under the DTSA, rather than relying on enforcement actions of the U.S. Attorney General’s Office, companies now can file private legal actions to protect their trade secrets and seek remedies from individuals or companies that infringe, steal or misappropriate them. The DTSA provides the necessary “teeth” to enforce these valuable rights.

As noted above, under the EEA any company in need of litigation regarding the misappropriation of their trade secret had to go through the U.S. Attorney’s office. By allowing the owners of trade secrets the ability to hire their own counsel, companies are in control of their own enforcement of intellectual property. Companies can also seek out lawyers that have a greater wealth of knowledge pertaining to trade secret law, providing them a benefit that a prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s office might not afford. Furthermore, the office of the U.S. Attorney juggles myriad cases at once involving many national issues – it thus cannot consistently give a company in need of trade secret litigation undivided attention. If the company hires its own private counsel, they can choose one who has the appropriate work ethic, knowledge and motivation to pursue the case. Thus, companies that take legal action regarding their trade secrets now are afforded the possibility of more attentive, accountable, and (quite possibly) knowledgeable attorneys- at least in the field of trade secret litigation.

2. There is now a federal (national) standard to use for trade secret cases. Much simpler than before.

The DTSA provides much needed uniform definitions for certain critical terms, most notably “trade secret” and “misappropriation.”

The DTSA definition of trade secret, for example, is rather broad. It allows protection of a wide range of proprietary information, specifically: “all forms and types of financial, business, scientific, technical, economic, or engineering information, including patterns, plans, compilations, program devices, formulas, designs, prototypes, methods, techniques, processes, procedures, programs, or codes, whether tangible or intangible, and whether or how stored, compiled, or memorialized physically, electronically, graphically, photographically, or in writing if (A) the owner thereof has taken reasonable measures to keep such information secret; and (B) the information derives independent economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known to, and not being readily ascertainable through proper means by, another person who can obtain economic value from the disclosure or use of the information.” This is very similar to definitions found in prior laws dealing with trade secret, such as the one found in in 18 U.S. C. 1839(3).

Acts that constitute misappropriation are also specifically explained in the DTSA, giving guidance to litigants as follows:

acquisition of a trade secret of another by a person who knows or has reason to know that the trade secret was acquired by improper means; or

disclosure or use of a trade secret of another without express or implied consent by a person who—

- used improper means to acquire knowledge of the trade secret;

- at the time of disclosure or use, knew or had reason to know that the knowledge of the trade secret was (a) derived from or through a person who had used improper means to acquire the trade secret; (b) acquired under circumstances giving rise to a duty to maintain the secrecy of the trade secret or limit the use of the trade secret; or (c) derived from or through a person who owed a duty to the person seeking relief to maintain the secrecy of the trade secret or limit the use of the trade secret; or

before a material change of the position of the person, knew or had reason to know that—

- the trade secret was a trade secret; and

- knowledge of the trade secret had been acquired by accident or mistake.

3. U.S. Companies Can Seize Assets and Freeze Business of individuals or entities that misappropriate their trade secrets (if they can make a strong enough case for it)

In addition to these uniform definitions and the ability to retain private counsel, section 2 of the DTSA granted owners of trade secrets the very powerful, though specific, right to seizures of personal property in order to enforce their rights. They may now act through court order to seize the assets and freeze the business activity of an individual or entity who is potentially misappropriating their trade secret, or disseminating information stolen from that company. This type of civil seizure generally occurs ex parte (meaning only one of the parties to the lawsuit, in this case the plaintiff, is in the court room) prior to a court formally finding misappropriation in the actions of a company against which a claim was filed. The court grants a TRO and seizure order. This seizure, though very useful and necessary in certain situations, must meet a laundry-list of criteria, in order to make reasonably certain that this ability is not used maliciously or in bad faith. In Conclusion… The most noticeable effect of the DTSA will be the ability of companies to privately pursue legal action against individuals or business entities that misappropriate their trade secrets. While the ex parte seizures (civil seizures) are exceptionally noteworthy, the instances in which they can be used are exceptionally rare, making them a useful, though seldom-used ally. The passage of the Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016 might not have made the front page, but it has radically changed the legal reality for U.S. companies that need to defend the trade secrets their business relies on. The Entire Language of the Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016 can be found here. [i] The following is the criteria necessary to be granted a court ordered ex parte seizure under the DTSA: – Order following Fed. R. Civ. P. 65 or some other equitable relief would have to be insufficient in order to obtain this order – Must be immediate and irrecoverable damage done if the seizure is not ordered and carried out – A denial of the seizure order must harm to applicant, and that harm must: (A) be greater than the harm to the person/entity against whom/which the seizure is ordered; and (B) significantly outweigh the harm done to any third party by such a seizure – Chance of success of applicant in showing that the person against whom the seizure was ordered indeed did misappropriate or conspire to misappropriate his trade secret is highly likely – The request by the applicant is reasonably particular as to the property in need of seizure, location, basically the extent necessary under the circumstances – The person against whom the seizure is ordered would attempt, or be successful at destroying, moving, hiding, or making his property unavailable through other means if he was served a notice by the court – Finally, the applicant has not already publicized his request for a seizure, which would counteract the purpose of an ex parte/ civil seizure in the first place Drew Harris is a rising junior at the University of Tennessee and an summer intern at Shrum & Associates. Drew’s goal is to attend law school and possibly practice entertainment law upon graduation.

Drew Harris is a rising junior at the University of Tennessee and an summer intern at Shrum & Associates. Drew’s goal is to attend law school and possibly practice entertainment law upon graduation.